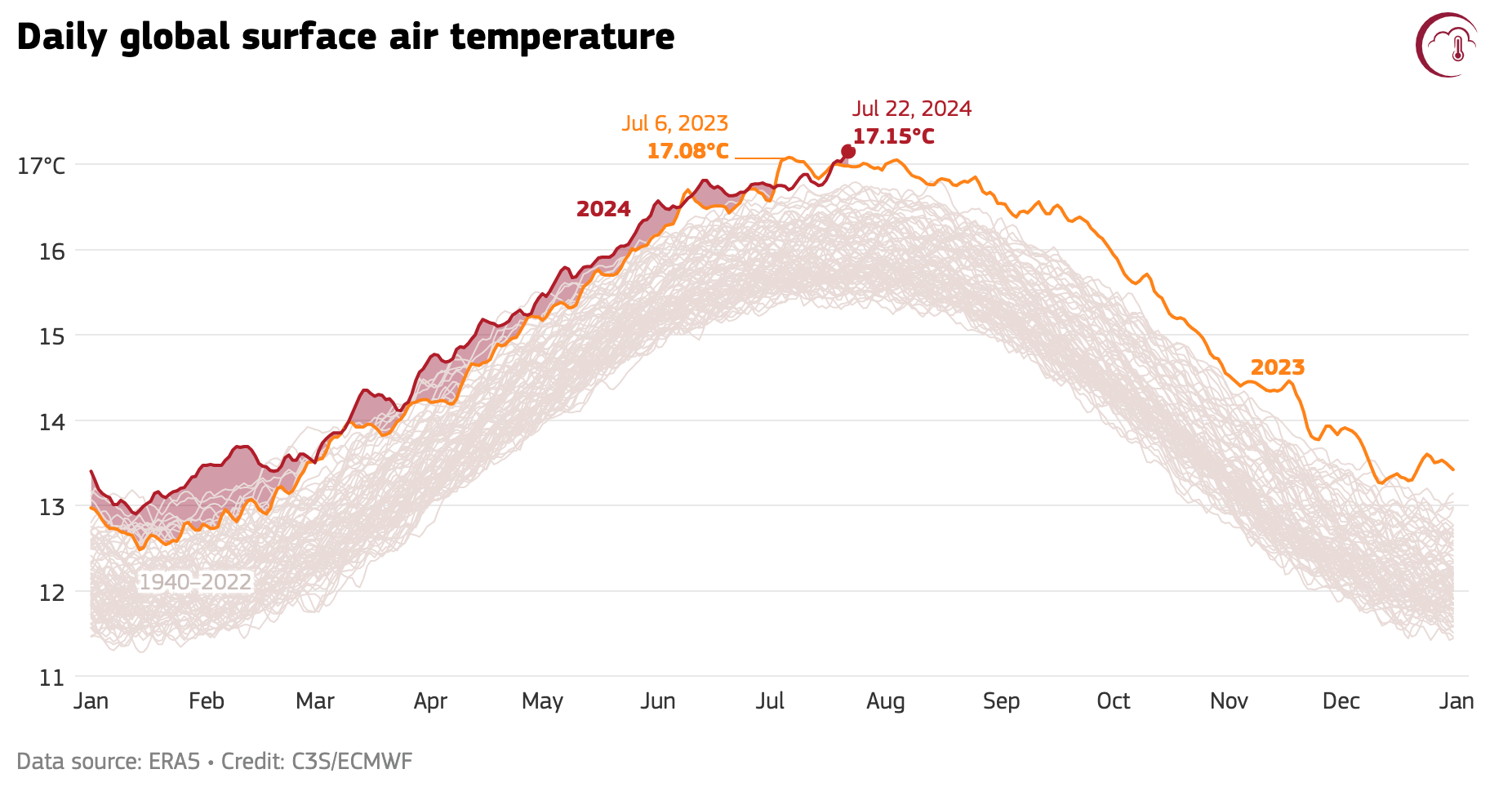

New world records are usually a cause for celebration, but not this one: Earth had its hottest day on record on Monday after average surface air temperatures hit 17.16°C (62.8°F), beating the previous record set just 24 hours earlier.

Global temperatures typically reach their peak this time of year, coinciding with summer in the northern hemisphere, where larger land masses warm up more quickly. But this particular peak is notable for a few reasons:

- It’s broken records despite the warmer El Niño phenomenon receding

- It’s broken records everywhere (1,600 places globally this week)

- It’s broken records quickly (the last records were in 2023 and 2016), and

- It’s broken records by so much (the red shading above shows the difference between last year’s records and those from 2016)

Of course, we’re International Intrigue (did we forget to introduce ourselves?), and we’re really interested in the international angle here. So here are just three that perhaps you haven’t pondered.

Stay on top of your world from inside your inbox.

Subscribe for free today and receive way much more insights.

Trusted by 114,000+ subscribers

No spam. No noise. Unsubscribe any time.

First, there’s the international tech that made this grim announcement possible.

The EU’s Climate Change Service (CCS) was the first to sound the alarm this week. It hoovers up vast quantities of data from the EU’s Copernicus, which uses sophisticated satellite groups (named ’Sentinels’) to help shape EU approaches to emergencies, borders, surveillance, and even the Russo-Ukraine war.

A lot of the Copernicus data is available to all, but the juicier info is for friends only, driving an increase in countries keen to be friends:

- The UK re-joined Copernicus after finalising Brexit

- Three US agencies have signed cooperation deals, as have players from Australia, Brazil, Canada, the Philippines and beyond, and

- Interestingly, Switzerland is keen but is delaying over the costs.

However, while the EU has built (and is still expanding) this successful Earth observer program in space, it’s still having trouble getting its satellites up there.

Officials were hoping the long-delayed French-led Ariane 6 rocket, which debuted this month, could be the answer. But that’ll take time – and the EU’s own weather satellite service has still just opted for SpaceX over Ariane 6.

Second, there’s the way government bandwidth, already stretched thin, gets stretched even thinner by a need for more – and bigger – emergency responses.

Just look at Typhoon Gaemi – Taiwan’s strongest in years – hitting right now: aside from the destruction, it’s also cancelled (for example) a Taiwanese dialogue in the US, plus air force drills back home. With China now periodically rehearsing a blockade offshore, Taiwan’s military drills and US dialogues aren’t just for fun.

And third, various data-driven studies have argued that countries more vulnerable to extreme weather events are also more likely to face conflicts.

A textbook example is the way Syria’s worst-ever drought (2006-11) pushed rural populations into urban centres, fanning existing tensions that spiralled into a civil war and sent millions of Syrians into Europe, where voter sentiment then shifted. That’s quite the butterfly effect from one indicator in one country.

So let’s bring this back to where we started, shall we? The boffins at Copernicus are expecting global temperatures to start the seasonal cooling process soon.

But over the longer term, they’re telling us we’ll keep breaking more records. And we’re already getting a peek at how that might shape our world.

INTRIGUE’S TAKE

The obvious question, then, is… what’s the solution? The world’s ‘COP’ climate talks in the UAE last year produced a breakthrough pledge to “transition away” from fossil fuels, but our consumption keeps growing.

And stunning growth in solar capacity keeps defying the forecasts, but (on aggregate) it’s still helping us expand total energy consumption, rather than displace our dirtier energy sources.

These are tough problems to solve, and yet government bandwidth to tackle the longer term causes risks shifting to address the shorter term symptoms.

So we can’t help but wonder if part of the answer might lie in more of the principles behind Copernicus above: sophisticated tech, open data, and practical partnerships.

Also worth noting:

- The EU Space Agency is planning to launch an additional two Sentinel missions (Sentinels 1 through 3 are already in orbit) to expand its observational capabilities.

- A key driver behind this week’s records has been higher Antarctic temperatures, 6 to 10°C (10.8 to 18°F) warmer than normal.